feature / exhibitions / art

March 25, 2020

By Stephen Nowlin

Shooting for the Sky: Williamson Gallery Exhibition Focuses on Humanity's Shifting Understanding of the Heavens

NOTE: Due to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, SKY is not currently available for viewing. We hope, however, that you enjoy this essay—with accompanying imagery—by the exhibition’s curator.

An immersive examination of how humans have conceptualized the sky throughout history, the group exhibition SKY demonstrates how new science is affecting change in the understanding of ourselves, our planet and beyond. SKY brings together works by West Coast artists—including Lia Halloran, Rebeca Méndez, Laura Parker, Christopher Richmond and Carol Saindon—with objects and artifacts from various museums and scientific archives—The Caltech Archive, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, European Space Agency—as well as a stunning piece of data visualization by Washington State scientist Eleanor Lutz. The following is an essay by the exhibitions curator, Director of Exhibitions Stephen Nowlin, from SKY’s mini-catalog.

First of all, let’s stipulate the sky begins underfoot. Wherever our planet’s rock and water surface ends, is where sky begins. With soles firmly anchored on terra firma, the cranium of a standing human is already in the sky, if not the clouds. We walk around like deep divers on the bottom floor of an airy sea.

Standing on Earth and gazing skyward, every day is actually a night bullied out of darkness by the glare of our nearest star, its fresh photons arriving after a mere eight light-minute journey. Entering an envelope of gases, the starlight’s shorter waves scatter and turn half the dome blue, obscuring the planet’s other half in a shadow that announces the glitter of space-time to anyone looking up. Other than from the screaming bright sun and a few fainter fellow-orbiting planetary neighbors, skylight captured by the naked eye of any earth organism may have begun its sojourn as long as 16,000 years ago—or 5 billion years ago for eyes aided by a big telescope’s glimpse into the deep past. The aphorism as opposite as night and day vaporizes in the realization that those two skies are distinct only by earthlings’ sight-lines to a single star.

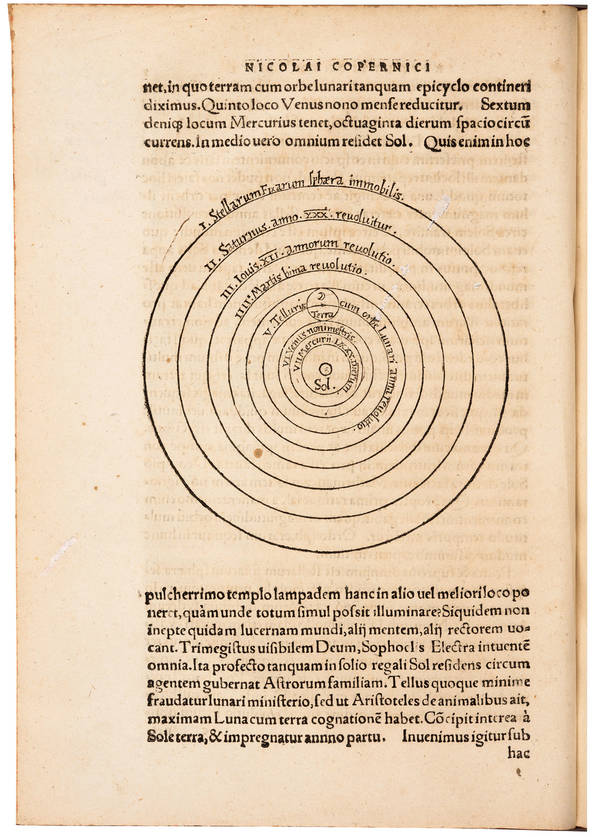

We’re pretty good at appeasing the day/night meme, so good in fact we lose touch with the clockwork and are lulled into the monotony of its circadian deception. The sun rises and sets (which it doesn’t), the moon sets and rises (which it doesn’t) and the stars swirl around us (which they don’t). The planet lumbers along at a gait too smooth to register, circumvolving its hidden axis and unacknowledged by the illusions we substitute. What really happens in the sky versus how we perceive it to happen are daily reminders of our minds’ susceptibility to the phantoms of repetitive normality.

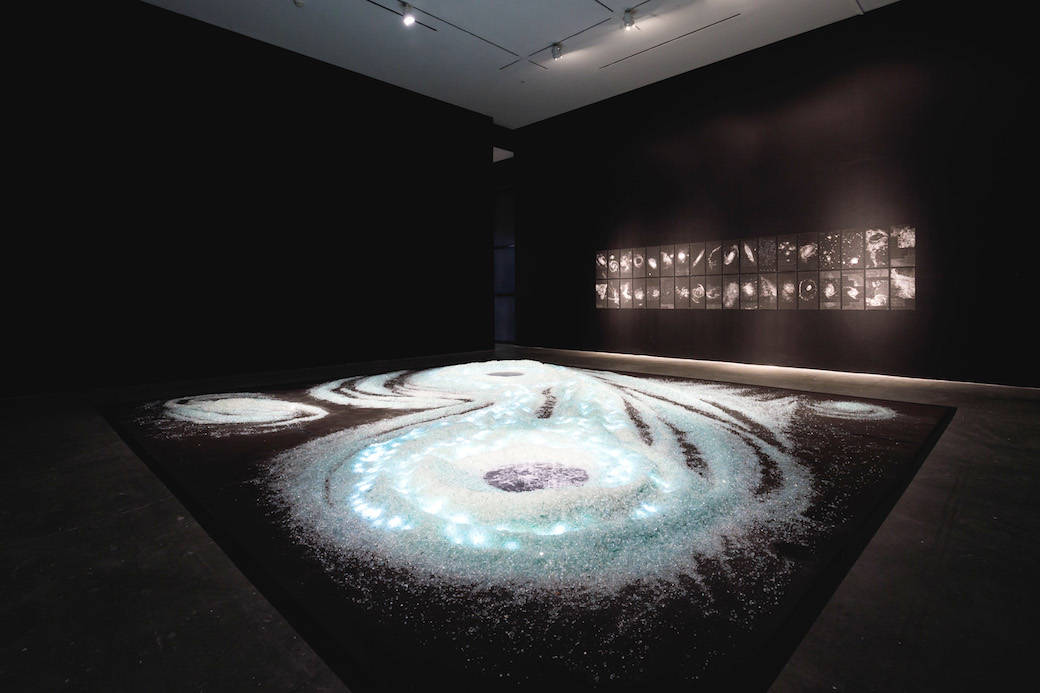

Outside of Inside, 2019

Floor/wall installation

Charcoal drawings, shattered glass, tar paper, 10 x 288 x 230 inches

Courtesy of Scape Gallery, Corona Del Mar

Photo: Juan Posada/ArtCenter

Into our sky, gravity shepherds flocks of space dust and debris—alien detritus from far, far away that also circle our big sky-star, skim too close to Earth’s gassy top, and end up wowing the dark half’s onlookers with a show of celestial fireworks. Without gravity, there’d be no trapped gas, no fireworks, no blue, no us, no planet, and no top 10 most popular weight loss programs. We’re captive to both the banalities and marvels of gravity’s bear hug. Its mysteries keep Earth’s mighty oceans from leaving the planet, washing into the sky and escaping to the great beyond. Its force is powerful enough to squash vast seas flat against the rock-hard terrain, yet so tender as not to harass a spider in its inverted trek across a kitchen’s ceiling.

Many up/down myths live in the sky. It’s the up there to which prayer is understood to ascend, like a helium balloon, into heaven’s heights and to an eternity from which the deceased are said to be peering down at us. It’s where many of history’s deities are said to have kept house and played out their Wagnerian dramas and unwitting neglect of physics, where they perched to keep tabs on their subjects stuck by gravity to the surface below, and it’s the yonder into which past gods evaporated and were replaced over eons by successive version upgrades. The residue of those heroic tales persists still in the up-nod of one’s head, the acknowledging up-glance of the eyes, and the ascending signal of thankful appreciation for having avoided some near disaster, played the right card or scored a fourth quarter touchdown. From the mists of up there, fate and fortune are apportioned. The sky’s the limit romances a yearning that anything shall be possible and a stockpile of helpful assistance from divinity, luck or destiny is stored far and away in the cloud, above the horizon.

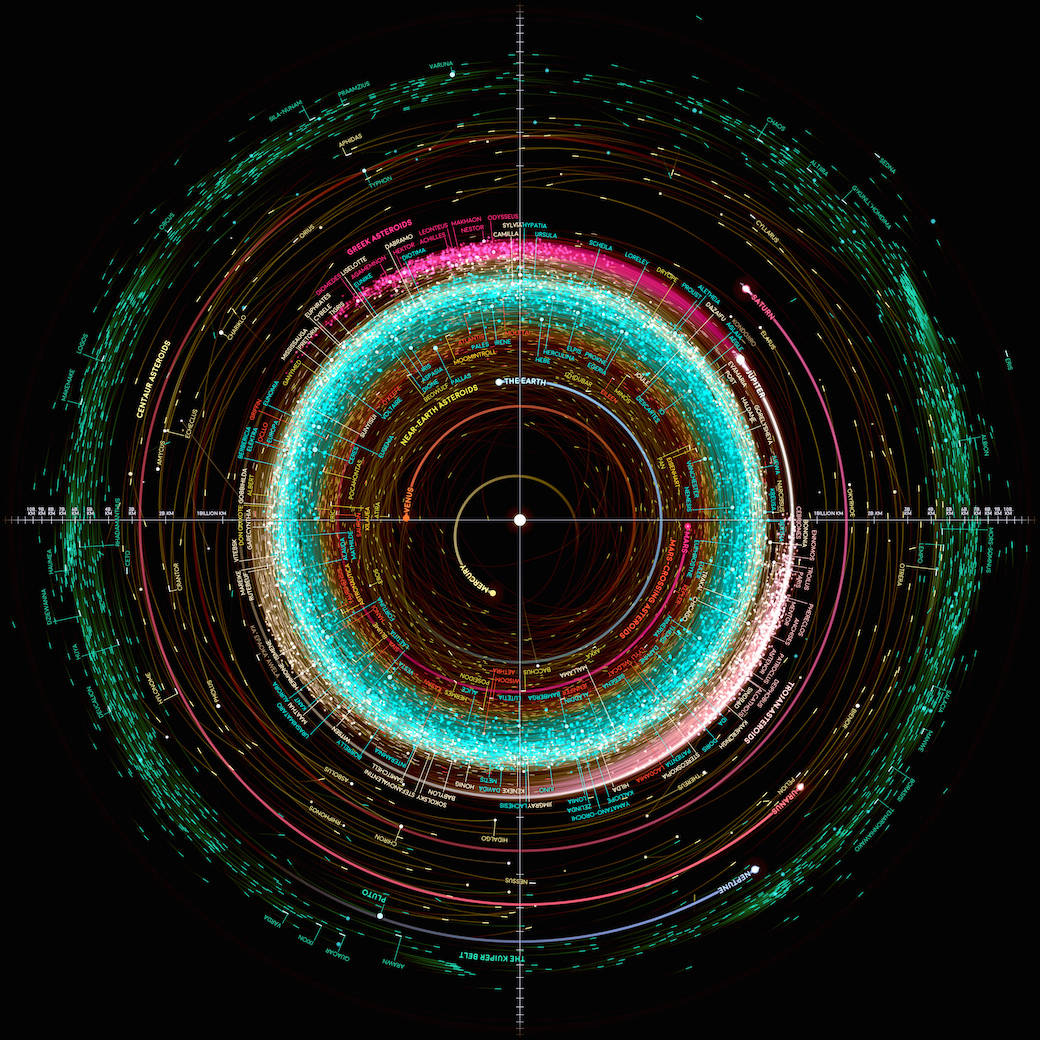

Orbit Map of the Solar System, 2019

Rotating wall projection, 96 x 96 in.

Courtesy of the artist and TabletopWhale.com

When we stand up straight on flat earth we cantilever into the sky at 90 degrees, buoyed by gravity, the mirror image of anyone standing half a planet away. We’re like tiny pins in a giant spherical cushion standing at someone else’s horizon no matter where we are, all of us conspirators in the deception that up is always the same up and down forever the same down. We spurn a flat Earth intellectually, and knowledgeably repudiate our ancient claim as center of the universe, but in a treaty with conceit we mostly behave as if both were still the case.

The mindset reinforced by what exists above and below the planet’s horizon line exemplifies a provincial weltanschauung, a conception of reality based on invariant dualities and sacrosanct polarities that are ostensibly self-evident: above/below, good/evil, us/other. The further parsing of these supposedly eternal binaries may raise fears of slippery slopes, or that once apparently settled simplicities will gain further nuance, evolve new subtleties and develop complexities that undermine ostensibly stalwart absolutes. But along with other human and social entanglements, the provincial sky of the past and its up/down, night/day bifurcation—the womb within which we were formed and through which we move and of which we breathe—is not the full world of the present where we continue to exist and imagine and compile meaning. Yesterday’s sky is being replaced by a blossoming sky now unfolding and revealing itself in time and knowledge. Today’s sky is multifaceted, more disheveled, more intricately difficult and wonderful. And, as recently discovered, today’s sky is much, much larger.

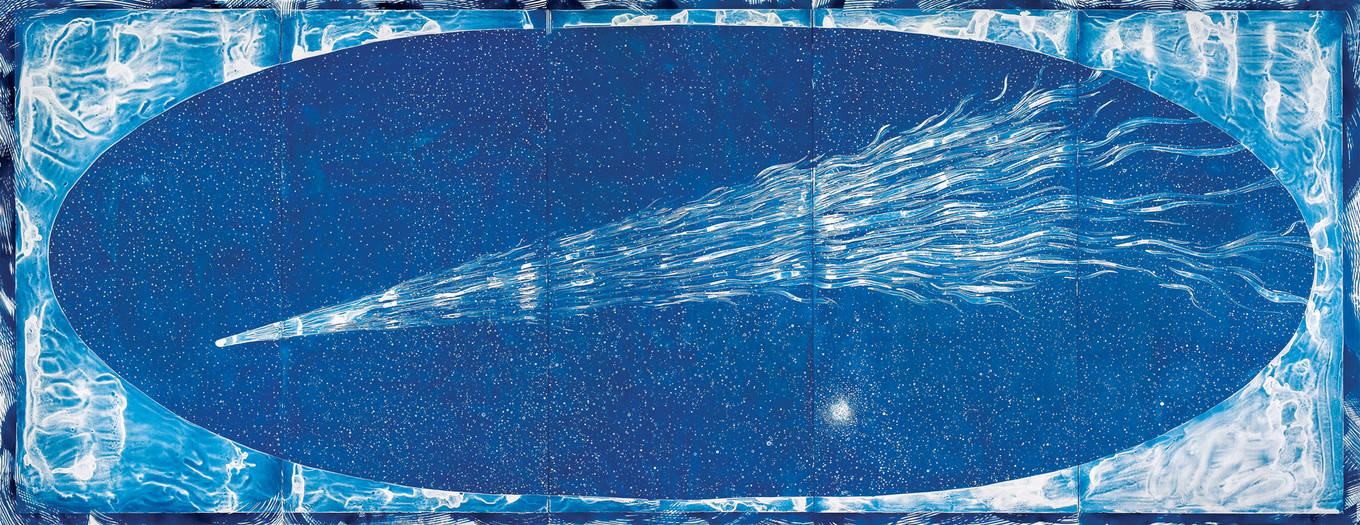

The Great Comet, 2019

Cyanotype on paper, from painted negative, 84 x 215 in.

Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles

In 1977, a gallon of gas cost 65 cents, the Apple II debuted with four kilobytes of RAM, and two rockets took off from Cape Canaveral with a mission to explore the outer solar system’s planets. Those two spacecraft, NASA’s Voyager 1 and 2, have since continued far beyond our neighboring giants, and in 2017 were approaching interstellar space—13 billion miles from us and at a speed of about 35,000 miles per hour. After traveling for decades, they continue their odyssey. In another 4,000 decades (40,000 years) from now they will have traveled 12,264,000,000,000 (about 12 trillion) miles further from home. Assuming a human lifespan of 75 years, the two Voyagers will have traveled the equivalent of 3 million lifetimes, stretched out birth-to-death, back-to-back. After all those eons and that unfathomable succession of human lives, they will have reached a point in the far reaches of interstellar space, at which the very nearest star to them will be . . . our sun. Still. Not until further journeying for another full 40,000 years, will the spacecraft have reached the star nearest to our sun in the Milky Way Galaxy, our closest very far away next-door neighbor Proxima Centauri.

And that doesn’t convey, not even barely, the enormity of the endless sky.

Viewing Stone, 2018

Looping HD video, sound, 30:08

Directed and conceived by Christopher Richmond;

Cinematography: Colin Trenbeath; Editor: Christopher Richmond; Music: Aileen Bryant; Asteroid: Evan Walker

Courtesy of the artist

Stars, gas, rocky chunks and dust have gathered in the space-time sky far beyond our provincial halo of blue, collecting into massive galactic colonies spiraling around black hole eddies of gravity. From a distance, we can observe clusters of those other universes in the gaps between our own galaxy’s stars, their whirlpool arms and bodies each defined by billions of suns and clouds of star-making dust assembled into arcing gestures of light. These mysterious worlds—years or centuries away—beckon to us. Up close, however, those suns are agonizingly far apart. The nearer it approaches, the more diffused and less articulated a galaxy would appear to human space travellers. Stars, lest the fate of Icarus, would be skirted around by their spacecraft, adding years to their journey. The swirling shining spectacle they beheld earlier from a distance would have dematerialized into open seas of black space once inside the galaxy, space appearing to have expanded into remote outposts of illuminated rock or gas and a twinkling spray of faraway pinpoints of light. A spaceship in another galaxy or in our own is virtually subatomic by comparison and swallowed in nearly endless horizons. Galaxies are unimaginably huge. Only as seen by our eyes from great distances do such amorphous landscapes coalesce into their spiral splendor and pageantry. Such is the sky that begins under our feet—sky hoarding its secrets and science, its puzzles and knowledge.

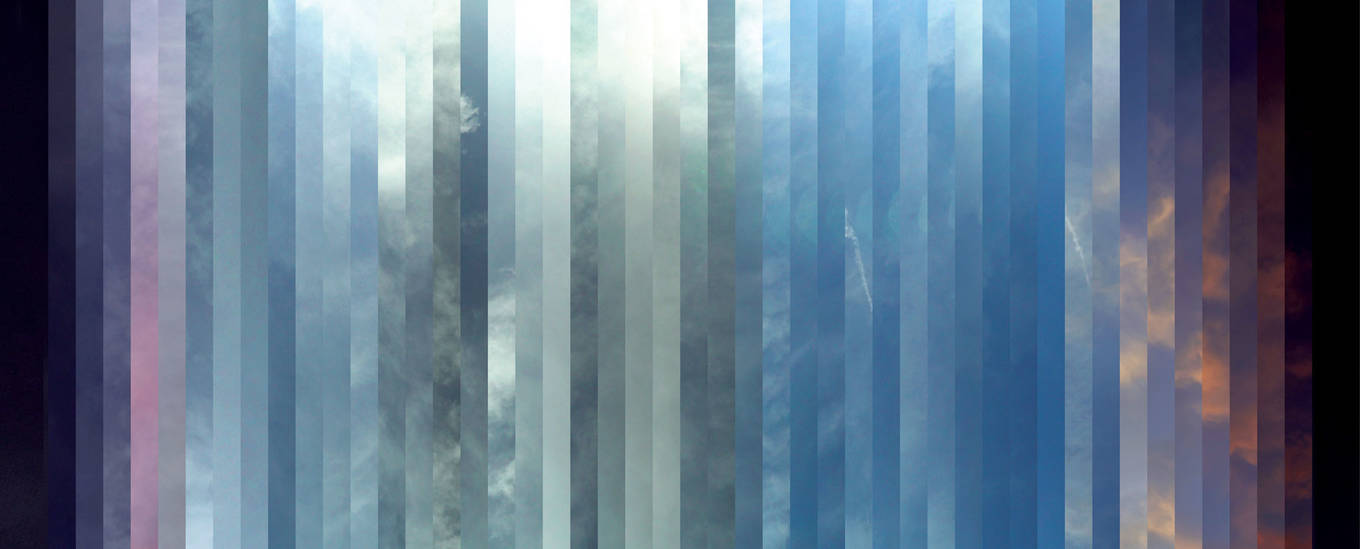

Any-Instant-Whatever, 2020

2-channel looping video, captured in Los Angeles in winter 2019–2020

15 x 36 feet, dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist

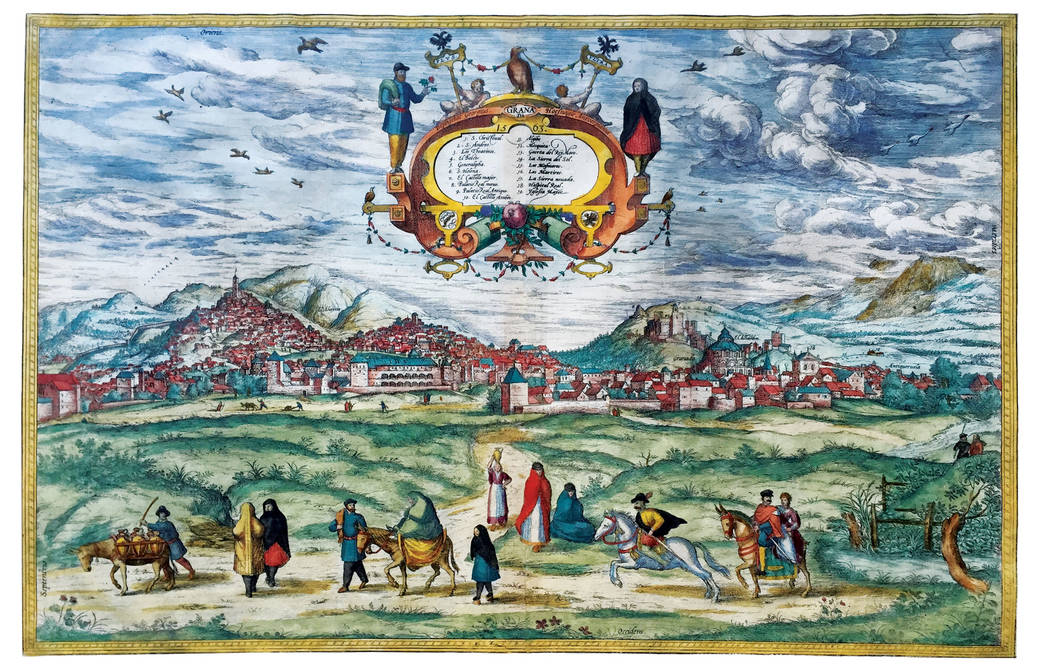

In artful depictions from humans’ deepest history to the present, sky is betrothed to land as its secondary counterpart. The sky is that heavenly space rising above the crusty shell of our primary abode where gravity assures our lives and dramas will play out. We’ve been distracted by the sky’s above/below illusions and fabrications throughout our long and inquisitive past, by mythologies and dichotomies invented from whole cloth and often lodged in the pictorial spaces of art. Art over time enshrines our habits of understanding the world—habits that carve out beliefs, guard their cultural authority, and become difficult to reshape. Among those, the provincial dualistic sky’s familiarity and dependable rhythm lulls like a rocking cradle, a drifting complacency, fortifying in us an expectation that what is routine is also immutable. But as science informs a deeper comprehension of how the world works and what the sky harbors, introducing uncertainties and weakening seemingly axiomatic conventions of thought, new art is also required to shatter and replace the past’s ossifying gaze.

Earth is not the floor of the universe, and no petty gods live in its sky. Nothing ordained swarms there, but its magnificence and mysteries summon emotions of transcendence nonetheless. It pulses with our intuitive and intellectual grasp of the intangible, an emergent sensation permitted not by whims of the divine but by the wonders of evolved biology. Most profoundly, we continue to consume sky. Desperately and fondly we return to the sky and draw it towards us, into our soulful sensations as well as our lungs, our veins and arteries. We bathe our cells in sky, and then give it back to plein air. Sky journeys through us, and connects us to what is boundless.

Moon, 2015

Archival pigment print, 16 x 60 1/4 in., framed

Courtesy of the artist

Related

feature

One for the artist books: Tomes exhibition explores the possibilities of the medium

September 27, 2019

feature