profile / alumni / photography-and-imaging / diversity / spring-2022

March 22, 2022

By Solvej Schou

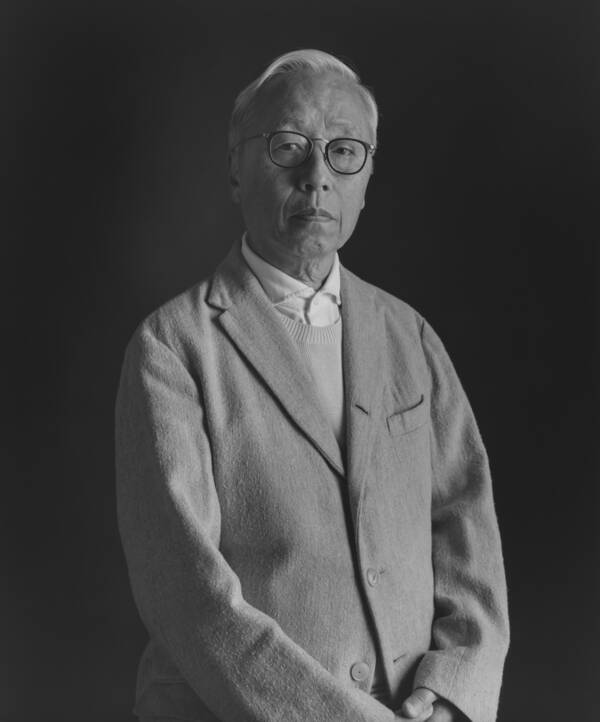

Images courtesy of Hiroshi Sugimoto

ALUM HIROSHI SUGIMOTO’S LEGACY OF PHOTOGRAPHY, ART AND EXPLORING HUMAN PERCEPTION

In one of artist and architect Hiroshi Sugimoto’s (BFA 74 Photography and Imaging) most celebrated photographs, a polar bear on an ice floe growls at a seal, its recent kill. Considering that 1976’s Polar Bear is actually a photo of a diorama at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the animals in it look staggeringly real, blurring the line between reality and fantasy, truth and fiction, life and death.

As with many of his photos, Sugimoto used a 19th-century style technical view camera with 8-by-10-inch black-and-white film and a long exposure time to create the beautiful shot. “Photography can be a time machine to investigate earlier stages of the human mind,” says the Tokyo- and New York–based alum from his home library in Tokyo. “I ask myself, ‘What is consciousness? What is the universe? Why are we are here?’”

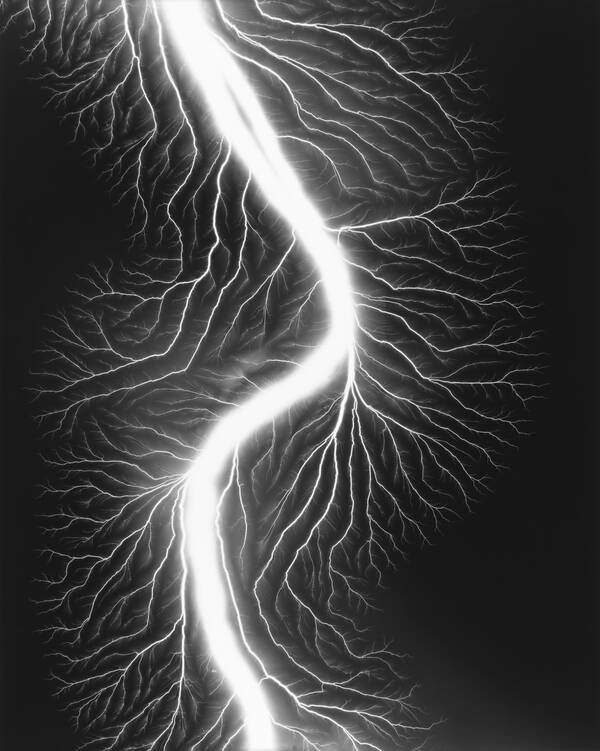

These philosophical questions drive Sugimoto, the recipient of ArtCenter’s 2021 Lifetime Achievement Alumni Award. For more than five decades, from Polar Bear to photos of seascapes and wax figures at Madame Tussauds to depictions of crackling electricity, his work has explored the intersections of nature, history and human perception. The New York Times has said of him, “Of all contemporary photographers, none has so rigorously explored the nature of his medium.”

ArtCenter, and being in California, was a key point in my life.

Hiroshi SugimotoPhotographer, artist, architect

In 2009, Sugimoto founded the Odawara Art Foundation to promote and cultivate Japanese art and culture. He also began directing and producing traditional Bunraku (a style of Japanese puppetry) and Noh theater. The foundation’s Enoura Observatory, which Sugimoto designed as both a performance space and a place to house his pieces, opened in 2017 on 60,000 square meters of land overlooking the blue Sagami Bay in the city of Odawara, south of Tokyo. Situated on a hill amid citrus tree groves and forest, the building features a 100-meter-long glass gallery that fills with light for the summer solstice, and a metal tunnel that faces the sun for the winter solstice.

“All of my work is interrelated,” Sugimoto says. “There’s a unique sense of space, whether applied to photography composition or to theater stage design. With the observatory, I wanted to create an ancient holy site—a reminder of our relationship to nature.”

Sugimoto’s creativity manifested early. Raised in Tokyo, he started taking photos when he was 12, using his father’s camera to capture images of trains as inspiration for his own train models. He also shot film footage of Audrey Hepburn from a movie screen.

As a young adult, Sugimoto was expected to take over his father’s pharmaceutical business, but he chose to go in a different direction. “I was kind of a Japanese hippie,” he says, smiling. He found out about ArtCenter, applied, and was accepted into the Photography program. His already skillful prints allowed him to skip two years of school.

“ArtCenter, and being in California, was a key point in my life,” says Sugimoto. “I learned so much about the technical aspects of photography.” He also spent time studying Japanese Zen Buddhism.

And taking LSD, he says, expanded the sensory capacity of his brain. “My perception changed with this tiny drug,” says Sugimoto. “Even since childhood, I’ve had strange, hallucinogenic visions. They scared me at first, but I decided to make them an asset.”

After graduating from ArtCenter, Sugimoto drove his van across the country to New York to work as an assistant to famed fashion photographer Ken Mori. But the commercial world wasn’t for him. He quickly jumped into doing photography as conceptual art—which was rare at the time. “With commercial art, you have to make images for everybody,” he says. “With contemporary art, you get to represent your uniqueness, your own reality.” Early 20th-century Cubist and Dadaist artist Marcel Duchamp influenced Sugimoto’s conceptual take on art and time.

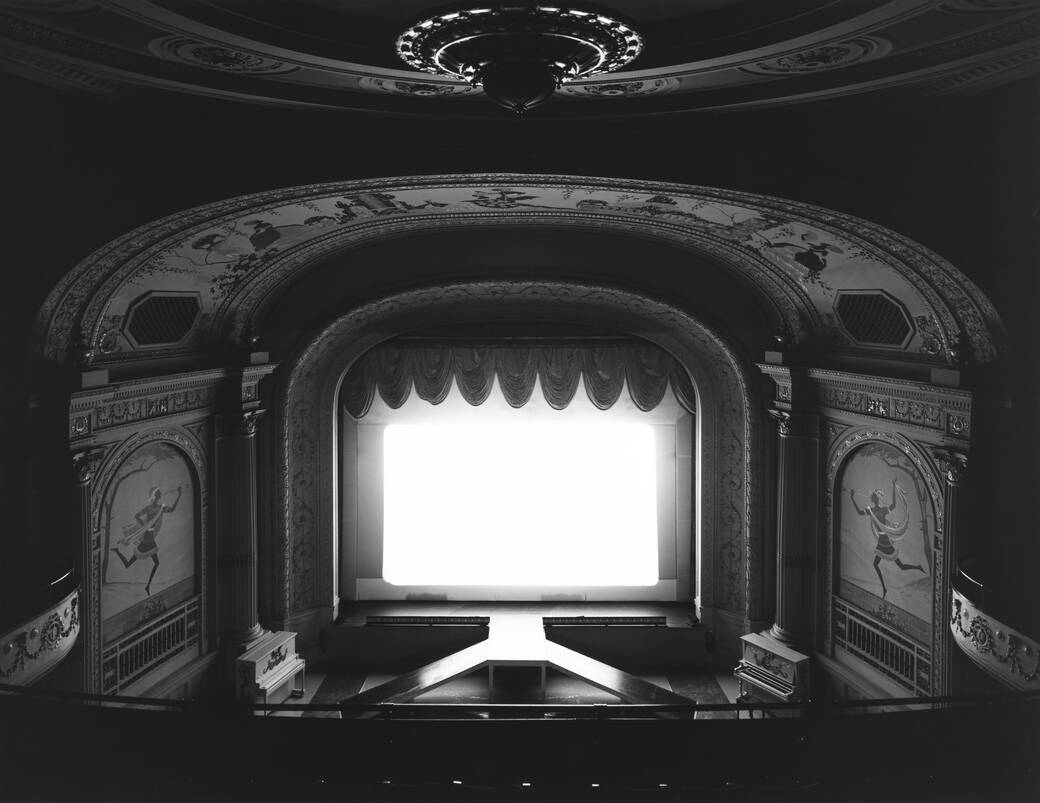

The Diorama series from the ‘70s—featuring Polar Bear, and sparked by a hallucinogenic vision Sugimoto had while looking at museum taxidermy—launched his career. Another hallucinogenic vision, he says, led to his striking and mysterious photos of blank, overexposed movie screens in dark empty theaters, a series he continued over decades.

In the late ‘70s, Sugimoto studied the nature-based Japanese religion of Shintoism, going alone into the forests of Japan. He then began to photograph the ocean. It took him a decade to nail down exactly how he wanted to photograph seascapes, and he eventually landed on capturing the serenity of the horizon, where the water meets the sky. “It’s always the vision that comes first, and the next step is how to make it happen,” he says.

For his ‘90s Portraits series, Sugimoto photographed wax figures of Salvador Dali, Napoleon Bonaparte, Anne Boleyn and others at Madame Tussauds in London and Amsterdam, presenting them in precise, living detail.

His later architecture work includes Glass Tea House Mondrian, which debuted in 2014 at the Venice Architecture Biennale. The piece was inspired by Japanese tea master Sen no Rikyū and abstract painter Piet Mondrian. An intimate, enclosed glass cube with wood elements, it sits above water, with a path of rectangular Japanese stepping stones.

Now in his 70s, Sugimoto has continued to shift and morph as an artist. He started writing songs several years ago. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he has written two books. After traveling the world for a decade, he’s stayed in one place for the past two years—the first time he has stayed anywhere for an extended period of time.

Sugimoto says that it’s only in the last 15 years that he’s been able to sell his work at a high price. Those sales funded both the Odawara Art Foundation and the Enoura Observatory.

“The observatory is my last piece, my legacy,” he says, “and I told myself to keep expanding it until the moment of my death.” He adds, with his eyes perking up, “I also have a new photography technique that I can’t announce yet—so you can still expect something new from me.”

Related

profile

Through heartfelt words and photos, alum Stella Kalinina reflects on her ancestral home in Ukraine

March 04, 2022

profile

Photographer and alum Erinn Holland on working harder and upending assumptions

October 27, 2021

profile