profile / alumni / illustration / artcenter-extension / spring-2020

December 12, 2019

WRITER: SCOTT TIMBERG

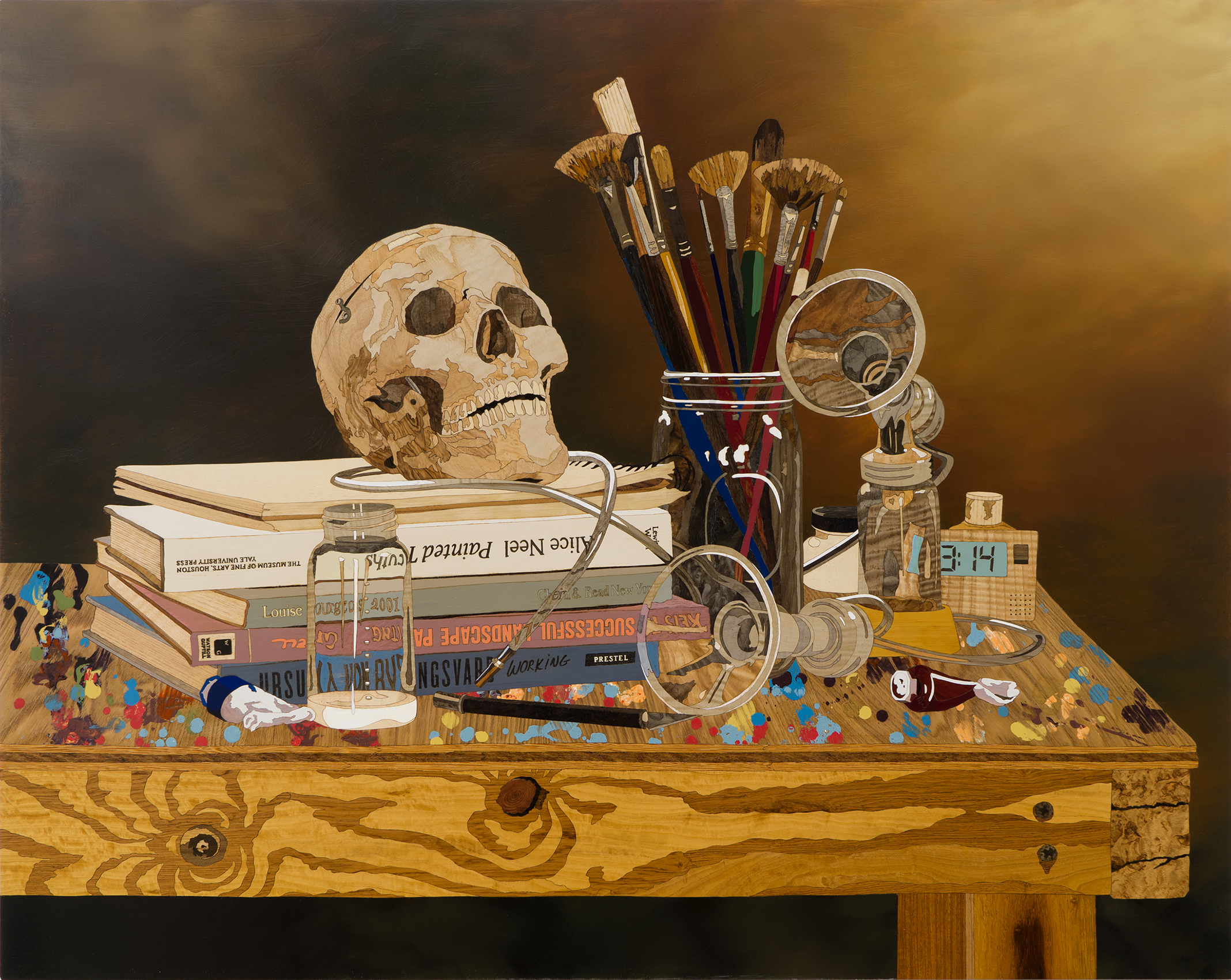

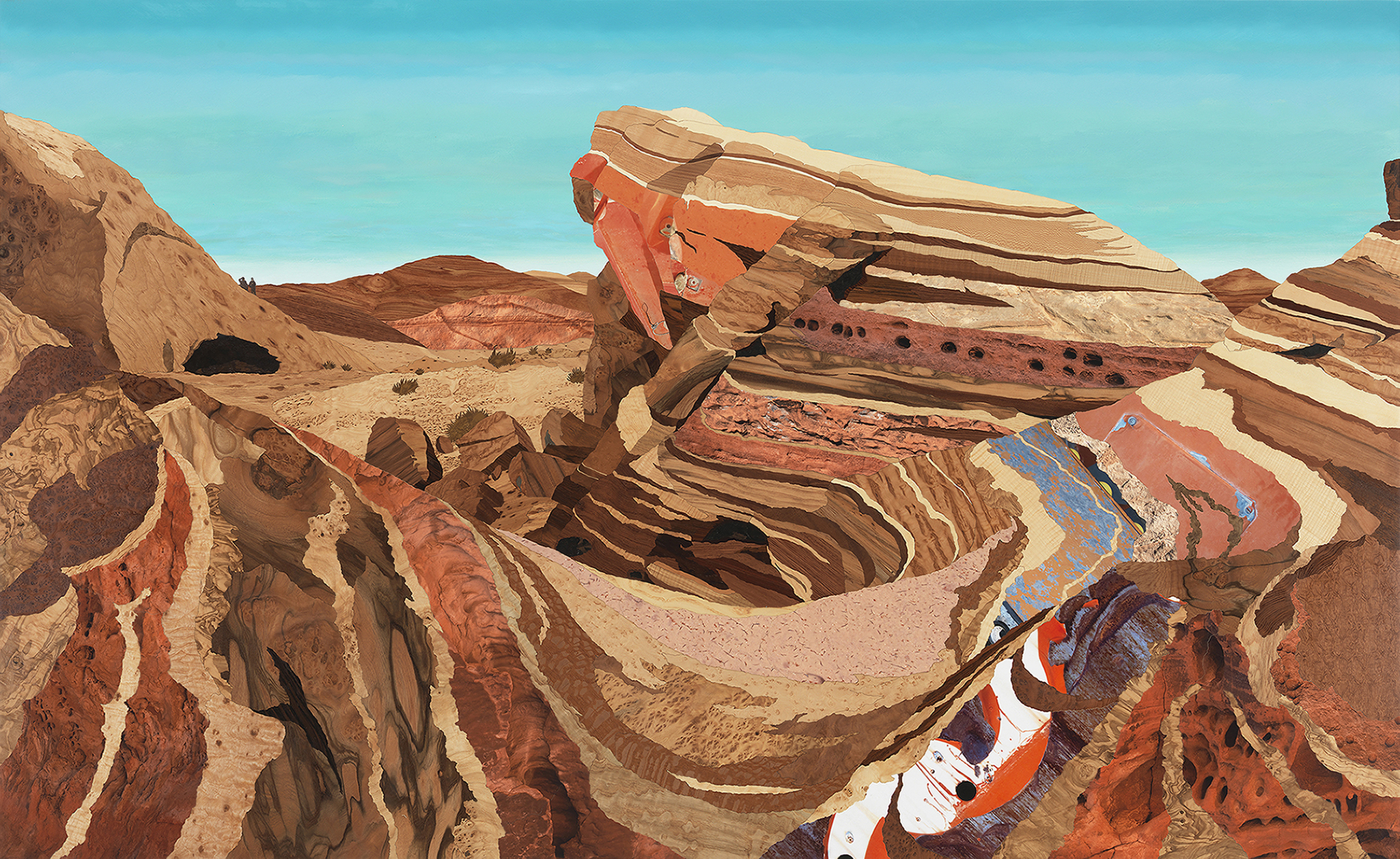

IMAGES COURTESY OF ALISON ELIZABETH TAYLOR

Alumna Alison Elizabeth Taylor Captures the Disappearing Landscape

When Brooklyn-based artist Alison Elizabeth Taylor (BFA 01 Illustration) returns home to visit family in and around her hometown of Las Vegas, she sees both more and less than she remembers: The open desert she’d played in as a kid seemed to be tattering while the city sprawls around it. Where she once saw “beautiful, endless mountain ranges,” she now saw tract homes and cul-de-sacs.

“Weather patterns are very different now,” she says. “A cloud of grasshoppers just descended on the Strip – it was almost Biblical.” Lake Mead, which feeds Vegas the way the Colorado River provides water for Los Angeles, “has gone down so much it’s got a bathtub ring.”

The shifting state of the place she once called home has inspired Taylor—an ArtCenter alum who’s made a name for herself working in the Renaissance tradition of marquetry—to approach the even-older tradition of landscape painting with new eyes.

Some of her pieces include bits of nature—a melancholy palm tree, desert hills illuminated by a queasy light—behind motels, gamblers, swimming pools or neon signs. (The effect is somewhere between Eric Fischl and Breaking Bad.) In a recent batch of work she hopes to show over the next year—of Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, now imperiled by the loss of federal protection—the embattled earth is the whole point. “They’re opening it up to oil and gas leases,” Taylor says. “It’s a nightmare; the ecosystem is very fragile.”

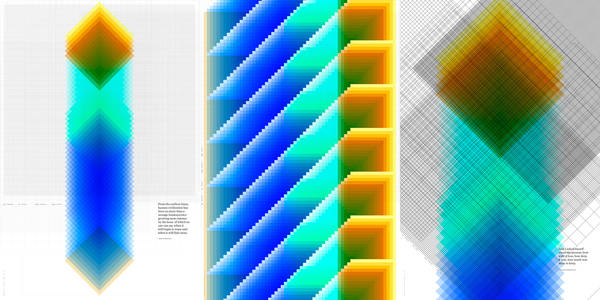

In April, four of Taylor’s pieces were included in the book Landscape Painting Now: From Pop Abstraction to New Romanticism. We seek in landscape, writes art historian Simon Schama, a place of myth, “a consolation for our mortality.” Taylor’s work seems to answer the question: What happens to landscape painting when the landscape begins to disappear?

Taylor came to ArtCenter after several years penning underground comics and working as layout editor at a weekly paper in Los Angeles. There was not much art in her Nevada upbringing, but she’d been turned on to visual storytelling by the work of graphic novelists Daniel Clowes and Julie Doucet, and wanted to learn more about painting and drawing.

At ArtCenter Extension (ACX), then named ArtCenter at Night—where she enrolled, initially, in her mid-20s—Taylor got what she calls “an old-school education,” but one that was entirely open-ended. Some days she’d work on 50 gesture drawings of a live model; other times she’d paint a scene in early-morning shadow and then again at the late-afternoon magic hour to see how light worked. The rigor and repetition paid off. “It makes you such an observer to do life drawing,” says Taylor. “You just learn to see. A lot of schools don’t do that.” But she also got to study with contemporary artists like acclaimed painters Rob and Christian Clayton, and by the end was working out her own ideas.

One day, she picked up a piece of wood-grain contact paper at a 99-cent store on Sunset Boulevard, and it piqued her curiosity about wood textures. Later, seeing a classic Italian work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art gave her a fuller sense of the possibilities of working with wood. Unexpectedly, Taylor became perhaps her generation’s leading practitioner of the old, very formal craft of marquetry, inspiring a 2008 New York Times profile, “An Artist Breathes New Life Into Renaissance Ways With Wood.”

Despite her reputation for marquetry, Taylor feels herself now coming back to painting: Even pieces built from hundreds of pieces of wood veneer typically have painted sections. Partly, it’s an aesthetic thing: “There’s such a nice contrast between flatness and depth,” she says. But it’s also because she was aching to continue the painting education she got at ArtCenter.

The resulting hybrid, art critic Barry Schwabsky writes in Landscape Painting Now, creates “an estrangement between her images and their vehicle. A disconcerting sense of artifice is the first thing her works convey, and then the specific content of the imagery filters more gradually through that."

The estrangement is important to how Taylor works. In fact, even before she began worrying about the ravaged environment, Taylor had a fraught relationship with landscape. Because much of what she saw before her art-school days was borderline kitsch—calendar art and bucolic, exaggerated nature scenes—“it made me not trust the form.” She also realized she couldn’t beat nature at its own game. “Why would I want to compete with nature, when a sunset was already so beautiful to experience?”

Taylor eventually came to terms with the genre. These days, she’s helping to redefine the possibilities of landscape painting in a fraught age. “For me it’s like the landscape was just a background,” she says. “But now it’s the foreground.”