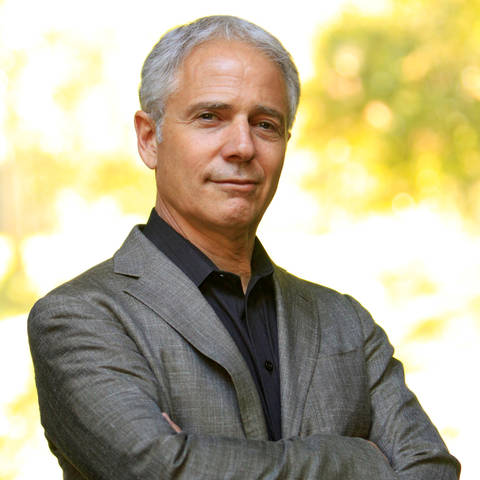

Lorne M. Buchman

Art Center president (and theater director) offers expert advice to creatives upping their presentation skills

It’s a chilly Wednesday morning in late November, and it’s showtime for a dozen students in Petrula Vrontikis’ Creative Presentations and Critiques class. Gathered in semi-darkness in the nearly empty Ahmanson Auditorium, they are joined by a few invited guests, among them Art Center President Lorne M. Buchman.

For their end-of-term critique, the 12 students will present 15 images for 15 seconds each—an abbreviated PechaKucha. Standing alone on stage and narrating their slideshows without a script, the students have all been given the same assignment, to trace their own individual journeys as artists and designers. For six of them, today is a rehearsal; for the rest, this presentation will be their final. Some are more nervous than others.

Vrontikis is a professor of Graphic Design, but she coaches students from across majors on communication and presentation skills, noting they are crucial to any career path–and like all skills, they can be improved. “Art Center students are so talented in what they present visually,” she explains, adding that what often needs strengthening is how they talk about their work.

To get things started, Vrontikis ascends the stage, microphone in hand, and steps into the spotlight. A model of centeredness, more like a yoga or meditation instructor, she takes a deep breath and lets it out. “Breathe in the lights,” she says slowly, looking out at her students. “They are your energy.”

Then, one by one, starting with Film major Chanzi “Ted” Wang, the students take their place in the spotlight, images projected onto a giant screen suspended behind them. Wang’s story begins in mainland China where he grew up, and takes him on multiple visits to Japan, inspired by a favorite Japanese TV comedy show. He makes friends there, but is also lonely. “Life is good, but life is also a son of a bitch,” he says, eliciting chuckles from the audience. “All of the bad and the good make me who I am.”

The digital slideshows assembled by the students move at a preset pace. Some students have so much to say, or such difficulty remembering what they intended to say, that they can’t keep up with the changing images. Each presentation is deeply personal, delivered with a willing vulnerability as students share memories—some difficult, some whimsical—of childhood or young adulthood. Family snapshots and favorite songs are in the mix, as are survival stories of rural poverty, medical crises, immigration and military service. One student who overcame especially tough odds offers her “key to a happy life” (“Why think things over so much? Just enjoy them.”), illustrated by a series of bright yet delicate drawings.

Buchman watches attentively from a sixth-row orchestra seat, occasionally jotting down notes. But as each presenter finishes and Vrontikis invites Buchman to share his feedback, he barely refers to those notes. Instead, visibly captivated, he addresses each student directly, occasionally hopping up onto the stage to stand face-to-face with them as he offers his critique, focused on questions fundamental to the success of any live performance: Who is your audience? At the core, what are you saying? What’s happening with your body language? What gives you authority on stage, what undermines that authority?

A Shakespeare scholar and theater director, Buchman has worked with Vrontikis on previous projects, including a student-organized TEDx event at Art Center in 2012, for which he served as an advisor as well as a presenter. His own stage presence is relaxed yet confident, and he now proffers the kinds of tips he might give an actor. Think about your posture, the position of your legs. Are you swaying or are you still? How are you holding the microphone, and what’s happening with your other hand? Listen to your voice—is it coming from high in your throat or from deep in your chest? A few deep breaths before speaking can help lower your voice.

He pointedly asks one student who has struggled to remember his script, “What’s the downside of memorizing?”

After a moment’s reflection, the student replies, “It distracts you. You see the thinking that is happening.”

“Where do you see it?”

The student hesitates. “In the face?”

“Especially in the eyes, right?” asks Buchman, looking directly into the student’s. “The eyes hold an enormous amount of authority in an engagement.”

Now pivoting to address the entire class, he drives home his point: “Never go off script if you have not fully memorized your lines. Otherwise, for the audience, it just becomes a guy trying to remember what he has to say. It’s the difference between remembering the actual moment you’re talking about, and remembering the script.”

What if, despite best efforts, one’s timing with the slides ends up being off? “Err on the side of staying with the slides and dropping text.” And if slides run longer than the text, or the text veers off course? “Pause,” says Buchman, then waits a long beat. “But you’ve got to play the pause. You need to communicate to your audience that the pause is intentional. Audiences are really forgiving with people who need to pause.”

He instructs one student not to move or speak at all, while he himself bobs and weaves animatedly around him. “So who’s winning this argument?” asks Buchman. “He is! He’s stock still.” The takeaway: There is power in stillness and in silence. And a corollary: If there is movement, make it deliberate.

One slideshow races forward at double the speed it should have, flustering an otherwise well-prepared presenter. Vrontikis makes it a lesson for the whole group. Soon they will enter the ranks of working designers and artists and so, she says, “I can’t emphasize enough how important it is for you to arrive early and test each piece of equipment ahead of time. It’s nonnegotiable.”

As students absorb the urgings and observations of their instructor and guest critic, they are sharpening some of their most important professional tools—the bodies and voices with which they will deliver and promote their work and their ideas.

The slideshows get attention too. Following each presentation, Vrontikis steps behind the tech operator’s table and peers into the open laptop used for projection. Her face illuminated by the small screen’s glow, she clicks through slides, fixes spelling errors, suggests the deletion or addition of material to heighten the impact of the presentation. She also questions specific image and word choices and their sequencing. “I need hierarchy here,” she says at one point, stopping on an especially cluttered text slide.

“You’re setting up the convention of a story told in words and visuals,” she reminds her students. “Stick with it. Stay with the connection between your visuals and your words. And know what your priority is.”

Also know what your secret is, Buchman adds. He calls it the most valuable piece of advice he ever received from an acting teacher: “If you’re not somehow telling the audience a secret about yourself, people will not be interested. The more you can touch into your own honesty, the more powerful your presentation will be.”

Toward the end of the three-hour session, Advertising major Alex Mon de la Guardia takes her turn on stage. She describes the painful surgery she underwent to have a titanium rod implanted in her spine, and shows a photograph of her bare back marked by a long vertical scar.

“Show the scar,” Buchman tells the group afterward. “It’s a wonderful metaphor for what we’ve been talking about this morning. To show the scar is not to show weakness, to say pity me, look what life gave me. It’s about the response to what life gave you. It’s not what happens to us, but how we respond to it.”