feature / graphic-design / diversity / spring-2020

April 14, 2020

By Solvej Schou

Raising Consciousness

Diversity in Graphic Design

In Displaced, a traveling performance piece created by New York City–based transmedia art and design studio Nonstudio, motion sensors and a body-tracking camera follow a modern-day Pandora in the form of an immigrant woman navigating the New World. She stretches, contracts and swings her body, boxed in by walls of light. Then she calls on the audience to shatter the walls.

“The walls represent the social constructs that bind us,” says Graphic Design alumna Pearlyn Lii (BFA 15), who co-founded Nonstudio with Connie Bakshi (BS 15 Environmental Design) in early 2019. Supported by New Inc, the New Museum’s cultural incubator, Nonstudio creates interactive installations, performance art and branded experiences that examine the female gaze and unspoken mythologies, including Lii’s own personal history.

Born in Hong Kong, Lii moved with her parents and her grandmother—who’s now 104—to the San Gabriel Valley, east of Los Angeles, when she was 4. Lii remembers curling up next to her grandma, who would tell her stories—narratives that would later impact the ethos of Nonstudio. “Her feet were bound, and she was one of nine wives,” says Lii of her grandma. “How can I reframe the biases around female identity when this is what I grew up with?”

For Nonstudio’s 2020 piece Reverb, which Lii describes as “a life-size hairy vagina,” the studio is partnering with a genetic technology company. Before entering the vagina, visitors sacrifice a string of hair, and then DNA is extracted and mapped to music. “The core of our work is inclusivity in feminism, and telling stories that embrace femininity, whether about mythologies, sexuality, hair,” says Lii, whose previous clients include Guggenheim Bilbao and Fashion for Good. “The freedom to be yourself—that’s what I want to celebrate.”

Graphic design in the 21st century is a multidirectional realm of possibilities. ArtCenter Graphic Design students today focus on a wide range of media and enter careers in which they design branding, packaging, environmental graphics, publications, UX, 3D motion graphics or, as with Lii’s transmedia projects, works that defy categorization. Yet the industry itself, in the United States, has historically not been diverse when it comes to who designers are.

“Graphic design as a profession can’t survive if it doesn’t represent the audience it’s speaking to,” says undergraduate and graduate Graphic Design Chair Sean Adams, the only two-term president of AIGA, the professional association for design, and an AIGA Medal winner who started an AIGA diversity initiative in the mid-’90s. “That audience is broad and diverse. And so is the future.” In order to represent and reflect that future—and the present—the industry must include women and people of different races, ethnicities, nationalities, cultures, disabilities, genders, sexualities, ages, economic status and religions.

In 1991, the AIGA put on a symposium that asked: “Why is graphic design 93% white?” Almost 30 years later, according to its 2019 Design Census, 61% of designers polled were women; 71% identified as White, 36% as Asian, 8% as Latinx or Hispanic, 5% as multiracial, 3% as Black, and less than 1% as Native American. Compare that to a 2019 Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data, which found that people of racial and ethnic minority backgrounds are projected to make up 56% percent of the population by 2060.

How does graphic design at ArtCenter compare? The Fall 2018 statistics for students enrolled in the College’s Graphic Design programs provide some answers. In the undergraduate program, 47% identified as Asian American, 10% as Latinx or Hispanic, 10% as White, and 1% as Black. Among graduate students, 16% identified as White and 9% as Asian American. International students made up 29% and 75% of undergraduate and graduate students, respectively.

As for gender, according to ArtCenter’s Fall 2018 statistics, women made up 64% and 67% of undergraduate and graduate Graphic Design students, respectively. In terms of faculty, according to ArtCenter statistics from Spring 2020, roughly 39% of the combined Graphic Design programs’ full-time and part-time faculty were women, and 61% were men. Adams says the departments are actively working on equalizing that female/male faculty ratio with top-notch designers.

“A lot of us are trying to create a space of inclusion and belonging that has yet to exist in our field, and in direct reaction to not having role models within the educational space and in the industry,” says Antionette Carroll, an equity designer and former AIGA national board director who founded the Creative Reaction Lab, a St. Louis, Missouri–based nonprofit organization that trains Black and Latinx youth to become leaders designing equitable communities.

Carroll was the founding chair in 2014 of AIGA’s Diversity Task Force, which conducted the first staff diversity training in AIGA’s centurylong history. She also co-founded the annual Design + Diversity Conference and Fellowship. Other industry efforts toward inclusion include AIGA’s Women Lead initiative, co-founded by ArtCenter trustee and AIGA’s fifth female president Su Mathews Hale, and 28 Days of Black Designers. Adobe’s Design Circle initiative—of which Carroll is an active member—has a mission of awarding tuition scholarships yearly to 10 people of diverse backgrounds. Boosting diversity also includes removing economic barriers, Carroll says.

“I went to school purely on scholarship, and it’s our job to provide scholarships that give students the same opportunities that I had,” says Adams, a CalArts alum. “We’ve also been reaching out to future designers earlier.” Graduate Graphic Design Associate Professor Jan Fleming, he says, has spearheaded an ArtCenter program developing a design curriculum for third-grade students—mostly Black and Latinx—at Maurice Sendak Elementary School in L.A.

Graduate Graphic Design student Kizzy Memani grew up loving art in Johannesburg, South Africa, and earned an undergraduate degree in architecture from the University of Cape Town before moving to the U.S. in 2017 to study at ArtCenter. For Memani, diversity in graphic design should be an obvious intention.

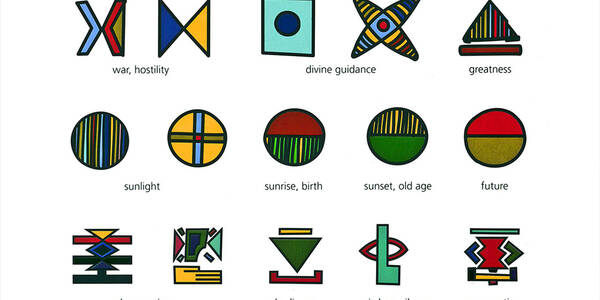

“I’m painfully aware that design is a symptom of an existing system,” says Memani, eating lunch at Mexican restaurant Yuca’s, a few blocks from the College’s South Campus, and wearing a T-shirt featuring his own typeface. “The design canon can be very monolithic and rooted in the same European history, and that needs to change,” he says. “You get tired hearing the same stories. The best story that I can tell that is different is mine. What’s most familiar to me is my experience as a Black guy in America who’s from a particular culture, from South Africa.”

Memani showed his work—a series of 16 vibrant experimental drawings of Black celebrities like Nina Simone and Danny Hathaway—as part of 2018’s Represent: Power in Color, an exhibition that explored representation through work by more than 20 ArtCenter students of color. The exhibition was held at the Armory Center for the Arts and presented by student groups Antiracist Classroom and CHROMA. “My series explored mental health in Black communities and the complexities of perception,” he says. “The kind of design I’ve always wanted to do fosters conversation and learning.”

After lunch, Memani walks to South Campus’ 1111 building to join other graduate students in Transmedia, a course taught by Associate Professor Carolina Trigo (BFA 98), a Buenos Aires–born artist, designer and researcher. Across a long table, Memani spreads out pages of text, based on conversations about gender with his friends, and then on a wall projects a video he filmed of a beer can, work boots and a condom—blown up like a balloon—being smashed. “It’s great that you’re questioning masculinity through objects,” Trigo tells him.

At the high-ceilinged L.A. headquarters of Atelier Ace, the in-house creative agency of Ace Hotel Group, staff graphic designer and Graphic Design alumna Jimena Gamio (BFA 17) sits next to coworker Juan Karlo Muro (BFA 17 Graphic Design). At her desk, there’s a sign that reads “SI” and a photo of pop artist and activist nun Sister Corita Kent. A nearby poster declares “EQUALITY.”

Born and raised in Lima, Peru, Gamio moved with her parents to Los Alamitos, California, at age 15, after her father lost his petroleum engineering job. She didn’t know English and started listening to punk bands to vent her frustration. “We would experience discrimination here because we had heavy accents and spoke Spanish,” she says. “I have always been very political because of my family, because I am an immigrant.” Obsessed with photography, collages and printmaking in high school, Gamio attended Cypress College, made short films, then spent a year at a trade school doing sign painting before being offered scholarships to ArtCenter.

Gamio’s student projects during the election of President Donald Trump—with his administration’s travel ban and promise of a border wall—addressed xenophobia head-on. In an Information Design course taught by her favorite instructor, Assistant Professor River Jukes-Hudson (BFA 05 Graphic Design), Gamio created the newsprint project Make America Great Again?, which juxtaposed Trump’s incendiary words against images of both his opponents and supporters. For an Advanced Print Studio course, which she petitioned to be taught by Assistant Professor Stephen Serrato (BFA 05 Graphic Design), she conceived a brand identity for the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles that included posters with slogans like “You belong just like any motherfucker living here” in purple type.

At Ace Atelier, Gamio designs a wide range of products, from signage to branding, posters and pop-ups. With her coworker Muro, she designed postcards with cutout images and hand-drawn lettering to promote an inclusive array of DJs at the roof bar at Ace Hotel Downtown Los Angeles. She designed a “Queer All Year” Pride Month sticker and tote bag sporting rainbow-colored type for Ace Hotel Palm Springs. A poster, part of a 2018 voting campaign she designed, proclaims, “You Have a Voice.” Gamio, who has a green card, reminded coworkers that the campaign should include those not able to vote.

“When I first started working here in early 2018, I was the only female designer on the team, and now there are four,” says Gamio, adding that the group has had many important conversations about inclusivity. “These conversations might be uncomfortable at times, but they open people’s perspectives.”

In her home office in the back of her house near Pasadena’s Rose Bowl, graduate Graphic Design alumna and freelance graphic designer Ziyi Xu (MFA 18) sifts through her work while reflecting on her journey to the U.S. On her wrist, she wears a bracelet made of red string—symbolizing luck—that her mom gave her. Born and raised in Suzhou, China, Xu studied digital art in Shanghai before getting her Graphic Design master’s degree at ArtCenter. She loves vivid color and proudly calls herself a maximalist designer.

“In China, my teachers spoke during critiques, and students listened,” she says. “When I came to ArtCenter, teachers asked, ‘What do you think?’ Getting used to that, and learning design terminology in English, was hard and took time. I used to be shy. Now I speak up a lot more.”

Xu’s newfound boldness is reflected in her work. For Serrato’s Advanced Print Studio course, she approached Martin Wong, the punk rock–inspired co-founder of Giant Robot magazine, to create a new identity and zine for his nonprofit organization Save Music in Chinatown, which throws all-ages shows to raise money for the L.A. neighborhood’s Castelar Elementary School. With swirls of yellow on red, the zine’s cover screams punk, featuring the letters “SMIC” stacked vertically. Xu based her design on the alphabet grid kids in China use to learn to draw Chinese characters.

Post–ArtCenter, her work includes TV commercial graphics cards for Chandelier Creative, where she’s also helping with translation, and designing the 2020 book Skullfuck: The Brutalist Cinema of Jon Moritsugu, a memoir by the Japanese American punk filmmaker. The title’s font—jagged and pink—resembles graffiti and reflects Moritsugu’s underground films, Xu says. The book’s publisher, Kaya Press, publishes cutting-edge literature that’s created throughout the Asian and Pacific Island diasporas.

“It’s been meaningful to work with Asian and Asian American clients,” Xu says, adding that she believes strongly in the importance of the industry embracing diversity. “Designers from different worlds have different creative perspectives. I have a fresh point of view.”