feature / alumni / faculty / students / graphic-design / interaction-design / media-design-practices / product-design / sponsored-projects

April 25, 2014

Writer: Mike Winder

Who, What, Why, When, Wearables

By now you’ve heard of Google Glass. But what about bracelets that measure sun exposure? Headphones that double as heartbeat monitors? Or jewelry that unlocks your front door? Are you ready for the dawn of smart watches, smart earrings, smart contact lenses and smart wigs? And no, that last one isn’t a joke.

The “wearables” field is in an early yet promising stage of its evolution. But ArtCenter, always striving to stay ahead of industry and cultural trends, has had wearables squarely in its sights for years. Today, our students, instructors and alumni are busy imagining where this technology might head next, creating the devices that are paving the way for the future, and questioning how a wearables-saturated world will change our behavior as human beings.

I want to use the body both as a platform and as a new interaction paradigm.

Jennifer Darmour Graduate Media Design Practices alumna

One big idea from the past decade driving today’s wearables is the quantified self, a movement that embraces the use of technology to capture and track an individual’s biometrics for fitness and health purposes. Examples of current products that tap into this growing market are the Nike+ FuelBand, the Fitbit and the Jawbone UP, the latter of which was designed by Product Design alumnus Yves Béhar’s (BS 91) Fuseproject.

Graduate Media Design Practices alumna Syuzi Pakhchyan (MFA 05), who runs the couture and circuits mashup blog Fashioning Technology and acts as a consultant for consumer electronics companies, says corporations are all curious about this growing space—Credit Suisse estimates the wearables market will grow from its current $3 to $5 billion to between $30 to $50 billion—and want to fit wearables into their business plan. But, she stresses, the technology is still in its infancy.

We’re used to interfacing with clunky products that influence their environment.

Jeff Higashi Instructor and Product Design alumnus

“The wearables out there right now are supposed to bring a level of self-awareness that leads to behavioral change, but they’re not quite there yet,” says Pakhchyan, who is also Media Design’s 2014 Technologist-in-Residence (more on that later), adding that most activity trackers have a one-month wearability rate. “The user experience around these trackers is a bunch of charts and graphs that are completely uninteresting. For most people, they end up in a drawer for the rest of their life.”

How can designers better integrate wearables into users’ lives? One person who may have an answer is Graduate Media Design Practices alumna Jennifer Darmour (MFA 05). A wearables veteran who has worked in the field for 10 years, Darmour runs her own wearables company, Electricfoxy, and is also a user interaction designer for Artefact, a Seattle-based technology product design and development company, where her clients have included Microsoft, Samsung and Google.

Darmour thinks wearables need to adjust to our needs, not the other way around. She believes strongly that many products today—ones that simply shrink down current technology and slap it on a wrist, or that force people to adapt to socially awkward user interfaces—are turning humans into cyborgs. Her solution? Design products that integrate technology into the fabric of our lives. Literally.

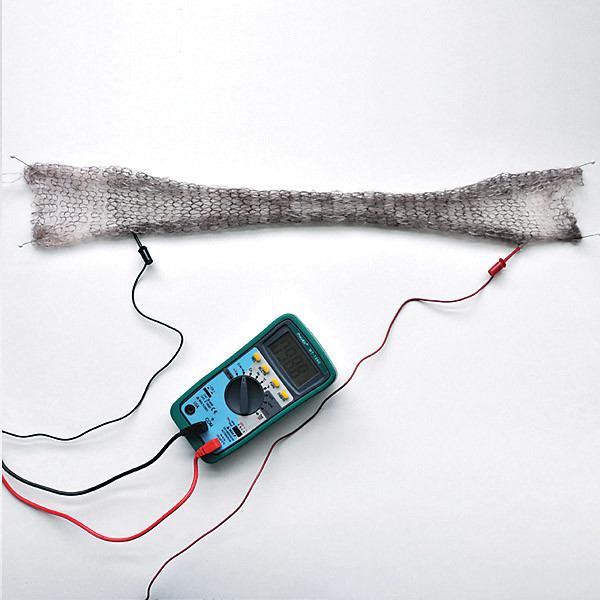

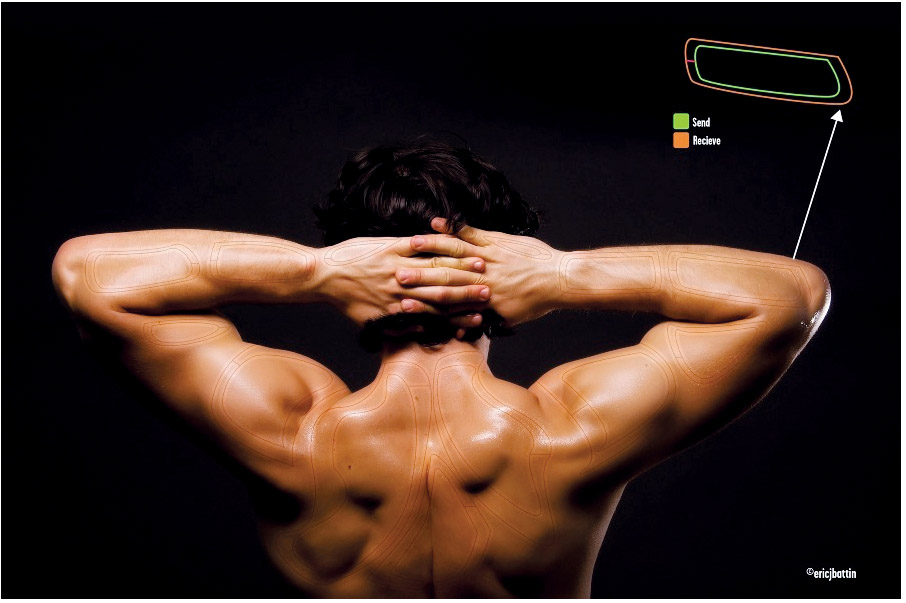

“I want to use the body both as a platform and as a new interaction paradigm,” says Darmour, and points to her Move smart garment concept as an example. Designed for people in yoga, Pilates, dance or other activities that require specific or expressive movements, Move is outfitted with four stretch and bend sensors located in the front, back and sides. The sensors read the user’s body position and muscle movement, and provide haptic feedback in the hips and shoulders to help correct the movements “in an ambient, precise and beautiful way.”

Darmour compares the wearables industry today to where the smartphone industry was in 2003. That was when the Blackberry smartphone made its grand entrance and helped to introduce advanced features like mobile Internet browsing and “push” email to the masses. Blackberry, however, was mostly targeted to information workers and productivity addicts. “My question is How do we create the iPhone of wearables?,” says Darmour, who points out that one of the major reasons Apple’s phone succeeded was that it created a platform for third-party developers. “How do we get wearables to that point? And how do we do it with products that are expressive, beautiful and designed the way we want them?”

No More the Stuff of Science Fiction

What if wearables were not only expressive and beautiful but could also save your life? That was the concept ArtCenter students explored in last Summer’s XPRIZE sponsored project, co-taught by instructor Brian Boyl and instructor and Product Design alumnus Jeff Higashi (BS 95).

In 2012 the XPRIZE Foundation launched the $10 million Qualcomm Tricorder XPRIZE competition to challenge teams from across the globe to design a device (or suite of devices) that provides an appealing and engaging consumer user experience and that can accurately diagnose a set of 15 diseases independent of a healthcare professional or facility.

The name comes from Star Trek’s tricorder, that noninvasive handheld medical device that could do everything from diagnose the common cold to monitor the vital signs of a crew member attacked by an aggressive reptilian (“He’s dead, Jim.”). The competition was based on the belief that the powerful processors and sensors found in today’s smartphones make tricorders seem less the stuff of science fiction and more a very tangible, and inevitable, outcome of current technology.

Thousands of individuals have participated in the challenge, including the 14 students in the College’s sponsored project, an activity which paralleled the main competition. The students created a number of concepts for wearables whose purposes included delivering insulin to Type 1 diabetic athletes, monitoring an individual’s blood pressure at work, and providing first-time parents with information on their newborns.

One team of students—Rachel Goldinger (Graphic Design), Andrew Cooper (Graduate Industrial Design) and Christina Hsu (Product Design)—created Cora, a device that helps users sleep better and reduce stress by creating an immersive chromatherapy nighttime ritual via a pair of video-equipped goggles. The Trojan horse aspect of this project is that Cora simultaneously captures the user’s retinal scans which contain information that, over time, can help doctors diagnose a number of issues related to the vascular, nervous and immune systems.

“The best part of this project is that it encourages people—through gentle, soothing reminders—to use this device and then it serially captures data over several months,” said Dr. Erik Viirre, the technical and medical director for the Qualcomm Tricorder XPRIZE who attended the students’ final presentation. “That’s where the medical information from the retinal scans is going to come. It’s going to be visible in small changes that the scans will pick up over months. That’s the real value.”

The Challenge of Creating a Better Experience

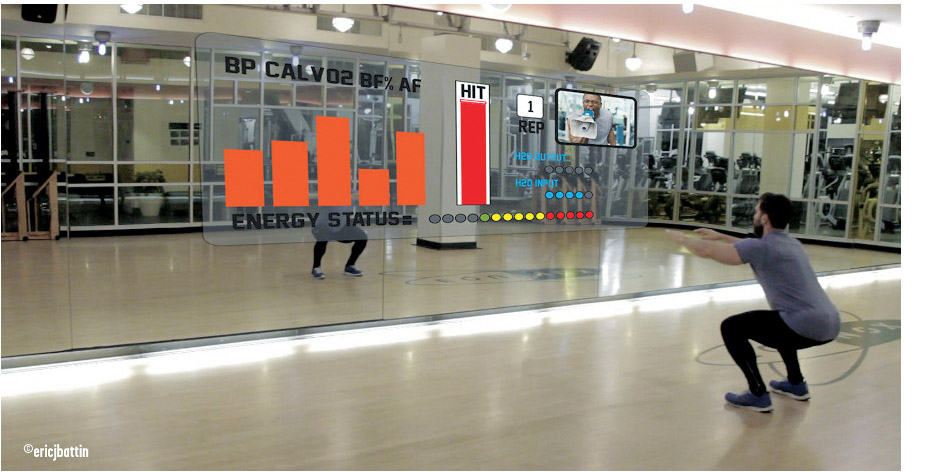

The XPRIZE sponsored project piggybacked atop Product Design 5 and Interface Design, a pair of concurrent courses that Boyl and Higashi have co-taught for the past two years. Product Design 5 focuses more on the design of the physical object, while Interface Design largely focuses on the visual elements of the interface, though the object and the interface are conceived as a cohesive unit from the beginning.

The two instructors have a wealth of experience in the field—Boyl’s background in interaction design goes back 25 years to when he developed software for Philips Interactive Media; Higashi has worked at Nokia and at Samsung’s LA Design Lab, and is currently vice president of product development at X2 Biosystems, a company that develops concussion assessment products for the NFL and the military. Over the past year, they have focused the classes specifically on health and wellness.

“The health and wellness focus allows the students to be either as clinical or as social as they want, which leads to a lot of innovation,” says Higashi, who adds that wearables are also a very attractive challenge for students, as current devices often feel unnatural. “We’re used to interfacing with clunky products that influence their environment. We’re looking for our students to ease that tension and to design a better interaction and a better experience.”

And the students’ efforts have attracted outside attention. ArtCenter students have been invited to participate in UCLA’s Business of Science Center’s Inventathon, where they will help students from UCLA’s Bioengineering Department discover unmet medical needs, design a related product and then pitch it to investors.

The Internet of (75 Billion!) Things

Also fueling the wearables market is “the Internet of things,” an evolving concept in which every object can be tracked and can communicate with one another. How many “things” are we talking about? Current estimates show anywhere from 30 to 75 billion devices going online by 2020, many of which will be wearables.

How will wall-to-wall wearables change our society? To explore this question, the Graduate Media Design Practices Department and pioneering technology company Intel co-produced a public symposium in February titled “Connected Bodies: Imagining New Wearables.” As one of five international institutions asked to join Intel’s inaugural Design School Network, ArtCenter has received to date $130,000 in gifts from the Silicon Valley company to investigate the relationship between design and technology, a portion of which supports MDP’s Technologist-in-Residence, Pakhchyan.

Organized by Pakhchyan, the symposium featured guest speakers including: Darmour; Product Design alumnus and director of design at Karten Design, Eric Olson (BS 96); Lama Nachman, principal engineer in Intel’s Interaction and Experience Research Lab (IXR); and Steven Holmes, Intel’s vice president of the New Devices Group and a former product director at Nike who launched the Nike+ FuelBand. The daylong event explored intriguing issues surrounding the complex nature of autonomous digital transactions; the ability of wearables to adapt to different contexts; and how this new wave of interactions should behave aesthetically and culturally.

“We’re attempting to discover what the interesting areas are for further investigation,” says Media Design Practices professor Phil van Allen, who along with his departmental colleague, associate professor Ben Hooker, co-taught the Intel-sponsored Connected Bodies course—which was conceived with Wendy March, design lead at Intel’s IXR, to run concurrently with the symposium. “We’re looking into the future, not trying to release a product tomorrow. In many ways, we’re trying to complicate the problem, not simplify it.”

We’re trying to complicate the problem, not simplify it.

Phil van AllenMedia Design Practices professor